Patients that sustain severe trauma are at high risk of mortality that comes in waves and may occur days to weeks after injury. Not only are patients at risk for dying at the time of injury, but a second wave of death occurs hours after the injury, from bleeding, and a third wave happens days later from systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) leading to multiorgan dysfunction.

Vanderbilt researchers have discovered that early inappropriate activation of the enzyme plasmin caused by severe injury is a trigger of SIRS and resulting organ failure leading to the third wave of death.

The findings, led by graduate student Breanne Gibson and reported in JCI Insight, suggest that pharmacologically blocking plasmin activity — at the right time — after severe injury could prevent the “cytokine storm” that causes the third wave of death, said Jonathan Schoenecker, MD, PhD, associate professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and senior author of the study.

Schoenecker and his team focus on determining the cause of adverse outcomes in orthopaedic surgery. In both elective and trauma-related orthopaedic surgery, these outcomes include early events like bleeding and thrombosis (clotting), and later issues such as problems with healing and tissue repair. Their ongoing investigations have revealed that these adverse outcomes occur, at least in part, from a continuum of dysregulated plasmin activity, which breaks down proteins including fibrin in blood clots and activates cellular responses.

“Plasmin is primarily supposed to be activated during tissue repair, days to weeks after an injury. If it gets activated too early, previous research has shown that it’s what causes the immediate bleeding problems,” Schoenecker said. “Now, we have discovered that this inappropriate early activity of plasmin also causes the systemic inflammatory response of severe trauma. And then, later, because it was activated at the wrong time, there’s not enough plasmin around for tissue repair such as healing a fracture or preventing fibrosis and heterotopic ossification (formation of bone in soft tissue).”

An inhibitor of plasmin activity called TXA is routinely used during orthopaedic surgery to prevent bleeding. To dissect the role of plasmin in inciting SIRS and the third wave of death, the group focused on severe injuries caused by a burn because early bleeding is not an issue.

In a study of burn patients, the researchers found that early activation of plasmin was associated with burn severity, inflammation, multiorgan dysfunction and death.

Then, Gibson and colleagues developed an animal model to mimic the conditions in burn patients. The researchers coupled a burn injury with a distant muscle injury (as a surrogate for other organs). When the muscle alone was injured, markers of inflammation went up and then resolved. But a burn injury at the same time — in a different location — caused persistent elevation of inflammatory markers in the injured muscle.

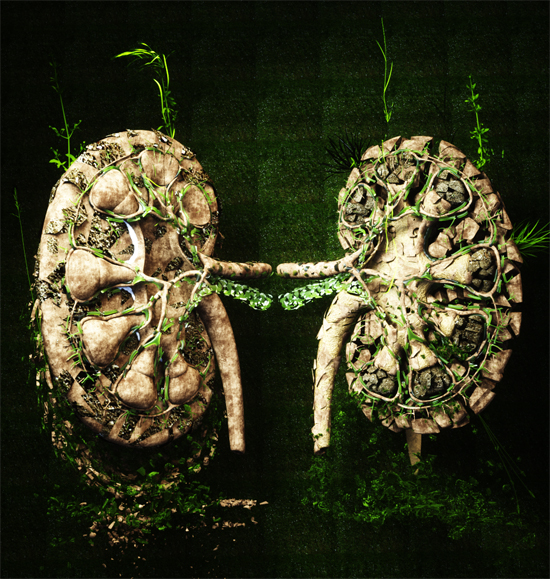

“This cytokine storm can be considered metastatic inflammation. The burn injury is completely dysregulating inflammation in other organs,” Schoenecker said. “We used muscle, but the same response is seen in other organs such as kidney, liver, lung and brain.”

Blocking plasmin activity with TXA or genetic methods restored the normal inflammatory response in the distant muscle injury and drastically reduced the cytokine storm.

“Inhibiting plasmin at the right time can prevent this metastatic inflammation that causes dysfunction of multiple organs and death after severe injury,” Schoenecker said. “Now we need to determine when, how much and how long to give TXA to block the adverse effects of early plasmin activation.”

The findings also have potential implications for other severe injuries, major surgeries and infections, including COVID-19, where inappropriate plasmin activation may be contributing to the SIRS response and multiorgan dysfunction, Schoenecker noted.

Other Vanderbilt authors of the JCI Insight study include Colby Wollenman, MD, Stephanie Moore-Lotridge, PhD, Patrick Keller, MD, J. Blair Summitt, MD, and Timothy Blackwell, MD. Schoenecker holds the Jeffrey W. Mast Chair in Orthopaedics Trauma and Hip Surgery. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants HL149340, AR059039, GM126062) and Caitlin Lovejoy Fund.