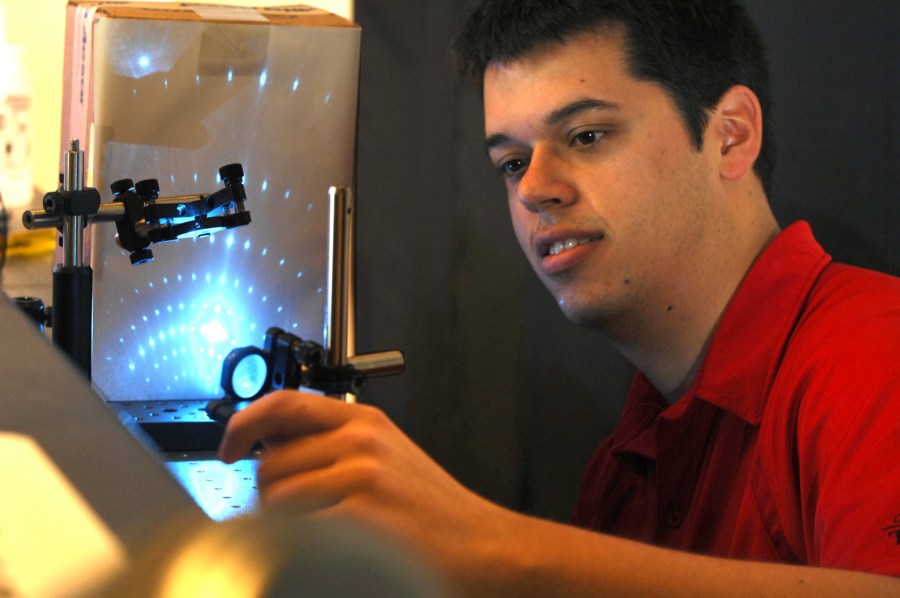

Graduate student Judson Ryckman demonstrates how one of the biosensors works that was made by the direct imprinting of porous substrates process. (photo by Anne Rayner)

VU scientists creating low-cost nanodevices

A simple technique for stamping patterns invisible to the human eye onto a special class of nanomaterials provides a new, cost-effective way to produce novel devices in areas ranging from drug delivery to solar cells.

The technique was developed by Vanderbilt University engineers and described in the cover article of the May issue of the journal Nano Letters.

The new method works with materials that are riddled with tiny voids that give them unique optical, electrical, chemical and mechanical properties. Imagine a stiff, sponge-like material filled with holes that are too small to see without a special microscope.

For a number of years, scientists have been investigating the use of these materials – called porous nanomaterials – for a wide range of applications including drug delivery, chemical and biological sensors, solar cells and battery electrodes. There are nanoporous forms of gold, silicon, alumina, and titanium oxide, among others.

A major obstacle to using the materials has been the complexity and expense of the processing required to make them into devices.

Now, Sharon Weiss, Ph.D., associate professor of Electrical Engineering, and her colleagues have developed a rapid, low-cost imprinting process that can stamp out a variety of nanodevices from these intriguing materials.

“It’s amazing how easy it is. We made our first imprint using a regular tabletop vise,” Weiss said. “And the resolution is surprisingly good.”

The traditional strategies used for making devices out of nanoporous materials are based on the process used to make computer chips. This must be done in a special clean room and involves painting the surface with a special material called a resist, exposing it to ultraviolet light or scanning the surface with an electron beam to create the desired pattern, and then applying a series of chemical treatments to either engrave the surface or lay down new material. The more complicated the pattern, the longer it takes to make.

About two years ago, Weiss got the idea of creating pre-mastered stamps using the complex process and then using the stamps to create the devices. Weiss calls the new approach direct imprinting of porous substrates (DIPS). DIPS can create a device in less than a minute, regardless of its complexity. So far, her group reports that it has used master stamps more than 20 times without any signs of deterioration.

The smallest pattern that Weiss and her colleagues have made to date has features of only a few tens of nanometers, which is about the size of a single fatty acid molecule. They have also succeeded in imprinting the smallest pattern yet reported in nanoporous gold, one with 70-nanometer features.

The first device the group made is a “diffraction-based” biosensor that can be configured to identify a variety of different organic molecules, including DNA, proteins and viruses. The device consists of a grating made from porous silicon treated so that a target molecule will stick to it. The sensor is exposed to a liquid that may contain the target molecule and then is rinsed off. If the target was present, then some of the molecules stick in the grating and alter the pattern of reflected light produced when the grating is illuminated with a laser.

According to the researchers’ analysis, when such a biosensor is made from nanoporous silicon, it is more sensitive than those made from ordinary silicon.

The Weiss group collaborated with colleagues in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering to use the new technique to make nano-patterned chemical sensors that are 10 times more sensitive than another type of commercial chemical sensor.

The researchers have also demonstrated that they can use the stamps to make precisely shaped microparticles by a process called “over-stamping” that essentially cuts through the nanoporous layer to free the particles from the substrate. One possible application for microparticles made this way from nanoporous silicon are as anodes in lithium-ion batteries, which could significantly increase their capacity without adding a lot of weight.

Vanderbilt University has applied for a patent on the DIPS method.

Vanderbilt graduate student Judson Ryckman, Marco Liscidini, University of Pavia, and John Sipe, University of Toronto, contributed to the research, which was supported by grants from the U.S. Army Research Office, INNESCO project, the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and a Graduate Research Fellowship from the National Science Foundation.