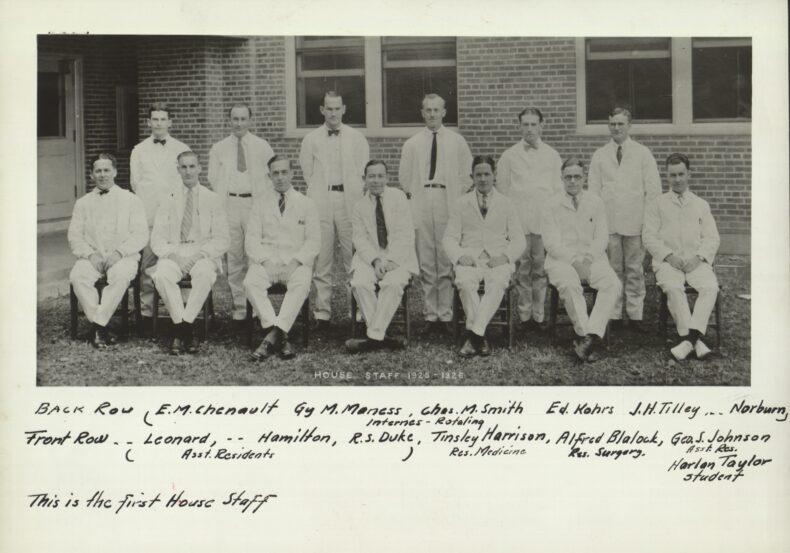

In 1925, the first house staff at Vanderbilt University Hospital included, front row, left to right: Bernard Leonard, MD, James Hamilton, MD, R.S. Duke, MD, Tinsley Harrison, MD, Alfred Blalock, MD, George S. Johnson, MD, and Harlan Taylor (medical student). Back row, left to right, E.M. Chenault, MD, Guy Maness, MD, Charles Smith, MD, Edward Kohrs, MD, J.H. Tilley, MD, and R.L. Norburn, MD. Note: Medical student Harlan Taylor found a spot in history when he slipped into the photo with the others. (Photo courtesy of the History of Medicine Collections, Vanderbilt University)

In 1925, the first house staff at Vanderbilt University Hospital included, front row, left to right: Bernard Leonard, MD, James Hamilton, MD, R.S. Duke, MD, Tinsley Harrison, MD, Alfred Blalock, MD, George S. Johnson, MD, and Harlan Taylor (medical student). Back row, left to right, E.M. Chenault, MD, Guy Maness, MD, Charles Smith, MD, Edward Kohrs, MD, J.H. Tilley, MD, and R.L. Norburn, MD. Note: Medical student Harlan Taylor found a spot in history when he slipped into the photo with the others. (Photo courtesy of the History of Medicine Collections, Vanderbilt University)

In September 1925, two rows of solemn-faced men in white coats lined up outside the new, combined Vanderbilt University Hospital and Vanderbilt University School of Medicine building for what is a historically profound snapshot of medical training in the South.

This was the first group of medical residents or house staff to begin their duties at the landmark health care facility just off 21st Avenue in Nashville (now Medical Center North). Here, they received instruction from nationally reputed faculty, cared for patients on the wards, worked alongside their mentors in research laboratories, and even ate their meals and slept at this location.

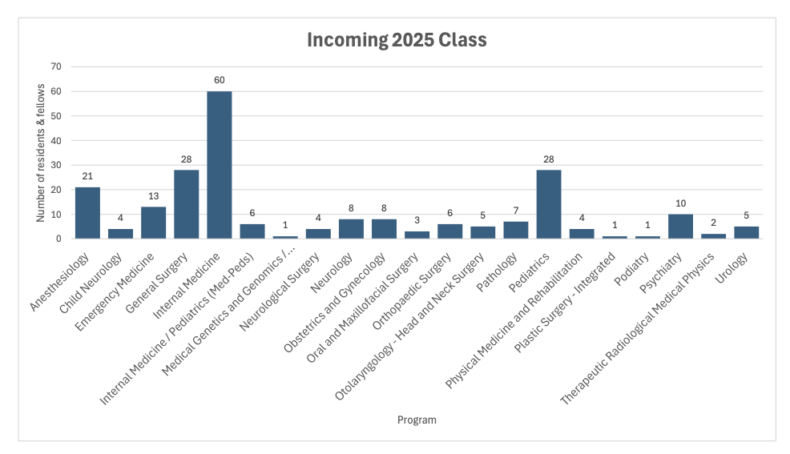

One hundred years later, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s graduate medical education (GME) program has grown from that inaugural dozen to include more than 1,200 individuals, with more than 170 highly competitive residency and fellowship programs, 107 of which are accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). At VUMC, residents are critical to the strong tradition of personalized patient care, fundamental translational and clinical research, and furthering the success of the health system.

“It’s remarkable to reflect back on a century’s worth of the contributions and continued successes of our house staff at Vanderbilt University Medical Center,” said Donald Brady, MD, Executive Vice President for Educational and Medical Staff Affairs at VUMC and Executive Vice Dean for Academic Affairs at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. “From the days of our residents living inside hospital walls so they could race to patient wards at all hours to our modern GME program that adapts to change, provides innovative training, addresses physician well-being, trains future leaders and develops highly skilled physicians devoted to quality care, VUMC has an impressive legacy.

“As our nation continues to face primary and specialty care physician shortages, evolving transitions in health care delivery, and funding uncertainty, our GME program is well prepared to meet these and other challenges head on. In today’s environment of ever-expanding biomedical science, innovations in technology and advances in therapies — all of which are well represented at Vanderbilt — I’m excited about the future for our house staff. Residency and fellowship are at the heart of medical training, and we will continue to support our house staff as they increase their expertise and become even more well-rounded clinicians.”

Home, Sweet Hospital

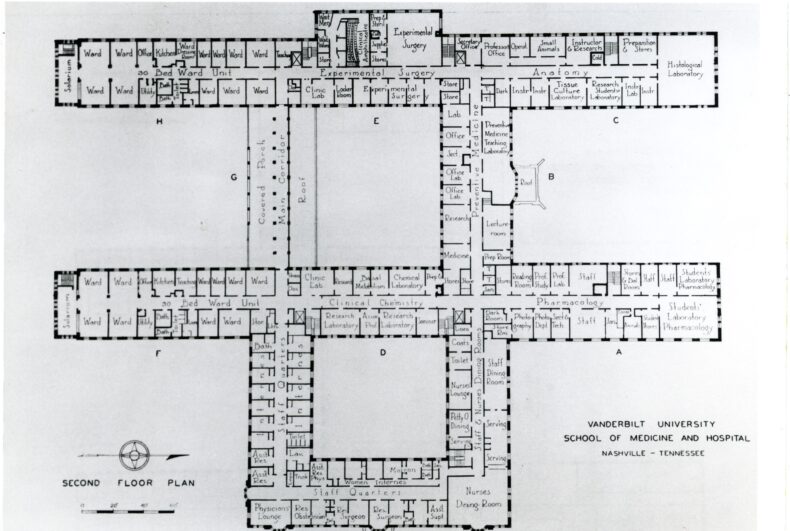

In 1925, the VUH and VUSM building, with its 208 patient beds, became a literal home for those first 12 men. They were “residents” or “house staff” after all. On the second floor, near the crossing of corridors B and S, there was a house staff dormitory. All house staff in those early years were unmarried and bunked together during off-duty hours. Female residents that would soon join the ranks had a segregated suite of rooms reached by a more private stairwell at the corner of corridors A and T. A small dining room adjoining the house staff quarters served residents and faculty alike, elbow-to-elbow at shared tables. Mealtime discourse often focused on challenging cases or promising research.

If the need arose, residents could be quickly roused from their slumbers by a hospital switchboard operator and refueled by black coffee. At the time, there was no air conditioning, so the building’s porches and courtyards provided a popular respite for patients and medical staff alike. Highly contagious pulmonary tuberculosis was the cause for many hospitalizations at the time. A long, open-air porch running between the B and C corridors on the hospital’s second floor provided the prescribed treatment of fresh air and sunshine.

Despite all of our advances in technology and artificial intelligence and devices and pharmacology and molecular biology and so many areas, the primary task of patient care is still performed by people.

Kyla Terhune, MD, MBA

Several of that initial group of residents would go on to achieve remarkable careers and mentor generations of physician-scientists. Particularly notable are Alfred Blalock, MD, Tinsley Harrison, MD, and Guy Maness, MD. Blalock was Vanderbilt’s first chief resident in surgery and became a pioneer in treatment of hemorrhagic and traumatic shock. He was the first to perform a subclavian artery to pulmonary artery shunt for congenital cyanotic heart disease. Blalock went on to train a generation of surgical leaders nationally, many of whom became surgical chairs.

Harrison, the first chief resident in medicine became a nationally recognized educator and is the namesake of Principles of Internal Medicine which continues to be one of the most widely respected textbooks in medicine. He later served as chair of the Department of Medicine at Wake Forest and the University of Texas Southwestern and dean of the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine. Maness established and became the inaugural chair of the Division of Otolaryngology at Vanderbilt.

Refining GME education

In the early years of U.S. residency programs, training was not standardized, and in addition to formal training in hospital-based programs, medical school graduates could opt to do a medical apprenticeship/internship or go abroad to study. Validating the quality and comprehensiveness of the education received was next to impossible.

In the 1940s, specialty medical boards began to grow, which created more defined and standardized pathways to medical careers. In 1952, the nonprofit National Resident Matching Program was established to facilitate the placement of U.S. medical students into residency training programs (a process known as “the Match”). Now, the program also includes the placement of international medical school graduates.

The triumvirate foundation of excellence in patient care, education and research that was laid a century ago here at VUMC continues into the future.

Sunil Geevarghese, MD, MSCI

The Vanderbilt tradition of strong peer and faculty mentorship, compassionate, evidence-based patient care and an emphasis on collaborative research has created a sense of family throughout the decades, and generations of medical students, residents and fellows have remained in Nashville to become VUMC faculty. Currently, approximately 30% of Medical Center faculty completed GME training at VUMC.

Brady is one former Vanderbilt resident who found a home as a faculty member. After graduating from VUSM in 1990, he completed an internal medicine residency at Vanderbilt. He then joined the faculty at Emory University, where he directed the primary care internal medicine residency program. He returned to Vanderbilt in 2007 as associate dean for Graduate Medical Education before promotion to his current role.

He recalls his VUMC residency and fellowship years with great fondness and credits the opportunity to mentor medical students during that time as a catalyst for his decision to pursue a career in medical education at an academic medical center.

“I loved it, and my experience of teaching medical students during residency and watching their progress reinforced my love for academic medicine. Fortunately, that aspect of mentoring and teaching is still core to who we are today,” he said.

In addition to steady growth in medical specialties training, Brady said another enhancement to today’s GME program is the addition of a weeklong orientation to better familiarize new house staff with the Medical Center and their role in the health system.

“We didn’t have a prelude to starting,” he said. “In fact, I remember showing up on the morning of July 1 and being told, ‘Here’s your schedule. By the way, you’re on call tonight. You’re at the VA, and you might want to go home, get a change of clothes and come back.’”

Just one month later, he was an intern in the medical intensive care unit at Vanderbilt University Hospital. Out of 24 beds, he was monitoring patients in 22 beds. It was the busiest service of his residency.

“I had some of the scariest and highest learning-curve moments of my life on that service,” he said. “Gordon Bernard was my attending, and he deepened my love for internal medicine.”

Other improvements to residency include an emphasis on well-being that is hardwired into the program at VUMC, Brady said. In 2003, in response to concerns about burnout as well as patient and physician safety, the ACGME announced guidelines to restrict resident work hours. At the time, interns (first-year residents) were on call on alternate nights and residents every third, with up to 36 hours of continuous duty. Now, residents can work a maximum of 80 hours a week, averaged over four weeks, with a 24-hour plus hand-off time limit on continuous duty.

Sunil Geevarghese, MD, MSCI, professor of Surgery, Biomedical Engineering, Radiology and Radiological Sciences and former vice chair for Education in the Section of Surgical Sciences, is a VUSM graduate who then completed a general surgery residency from 1994 until 2000 under the mentorship of John Tarpley, MD, professor emeritus of Surgery and Anesthesiology.

In Geevarghese’s office, photos of mentors as well as others he respects are placed so they continuously look over his shoulder. There’s VUMC’s Tarp, as Tarpley is affectionately known; renowned liver transplant surgeon Ronald Busuttil, MD, PhD, who trained Geevarghese at UCLA; and pioneering cardiac surgeon Blalock.

As he oversees and mentors surgical house staff today, Geevarghese acknowledges many positive changes since his days as a resident. During his house staff years, he said there was an emphasis on “selflessness and doing whatever it takes for the sake of the patient,” even if that meant your own personal interests and health might be compromised.

“Today, we try to support our residents and fellows in having the opportunity to rest and have time off for their health and well-being,” he said. “And I think that makes for a smarter, more compassionate workforce, without compromising patient care. As surgical educators, we try to ensure those elements of humanity are preserved for our trainees who are working so hard to take care of others.”

As a surgical historian, Geevarghese notes priorities that have remained constant over the last century, such as continuing to lead in innovative research and clinical care, which in turn attracts the best of the best to residencies and fellowships at VUMC.

“The triumvirate foundation of excellence in patient care, education and research that was laid a century ago here at VUMC continues into the future,” Geevarghese said. “Vanderbilt has trained, cultivated and hired so many excellent physician-educators and researchers across so many disciplines who have made major impacts across the world.”

Building future faculty leaders

Kyla Terhune, MD, MBA, associate dean for Graduate Medical Education for VUSM and Senior Vice President for Educational Affairs for VUMC, stayed on faculty after completing general surgery residency and critical care fellowship at VUMC. She served as program director of the surgery residency from 2014 until 2019 before stepping up to lead the GME program in 2019.

One recent initiative begun by her predecessor Brady, in partnership with colleagues at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, is the GOLLD Project (Goals of Life and Learning Delineated): Collaboration Across Academic Health Systems to Better Align GME with Learner, Patient, and Societal Needs.

As part of the $15 million American Medical Association Reimagining Residency initiative, the GOLLD Project addresses professional identity development in GME. The model, which is easily translatable to other medical centers, trains residents and fellows in population health, health systems sciences, and leadership and advocacy — and uses them to support their career development.

“The whole concept is to take residents or fellows who we identify as future faculty and provide them additional professional development,” Terhune explained. “We assume they’re going to get exemplary training through their clinical training program, but this further encourages them to include health system sciences, population health and leadership. Each one of them has a capstone project with mentors throughout that process. We then distribute their capstone pitch to the relevant leaders throughout the Medical Center.”

GOLLD participants, who gain invaluable networks and understanding of how VUMC works, are potentially more recruitable as faculty, more invested in the institution, and also have a jump start on their careers, Terhune added. The initial cohort was more likely to stay at VUMC than their counterparts.

Terhune often compares the GME programs’ offerings today to her time as a resident and fellow. While the volume of information house staff has at their fingertips has multiplied exponentially, technology is advancing at a rapid pace and treatments are evolving continuously, some things will always be the same, she said.

“Despite all of our advances in technology and artificial intelligence and devices and pharmacology and molecular biology and so many areas, the primary task of patient care is still performed by people,” she said. “Our residency and fellowship programs are growing people to interact with all of those elements but to still be compassionate, thoughtful, professional, mature individuals. Our residencies and fellowships are still about training humans to take care of humans. Vanderbilt continues to lead in this essential mission — and will continue to do so in the years to come.”