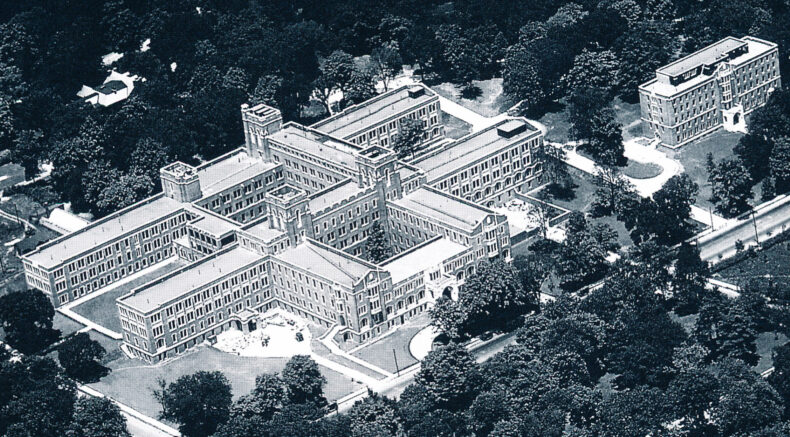

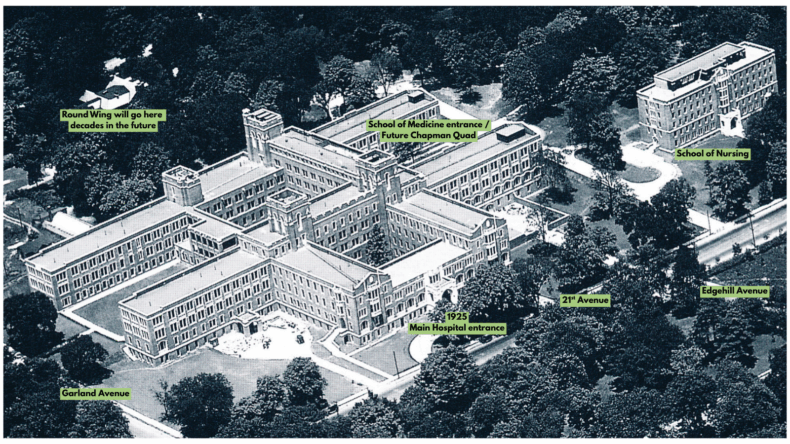

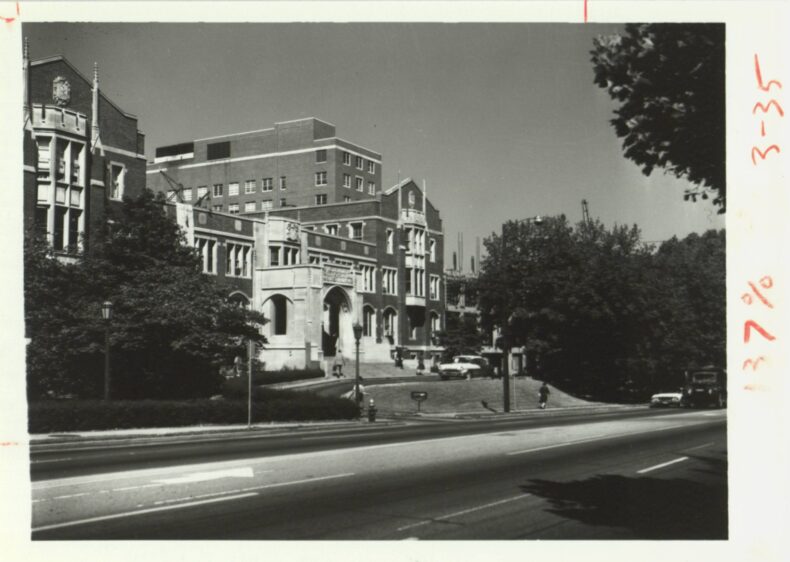

The building on the Main Campus we now call Medical Center North (MCN) opened on Sept. 16, 1925, and for many decades it, for all practical purposes, was Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

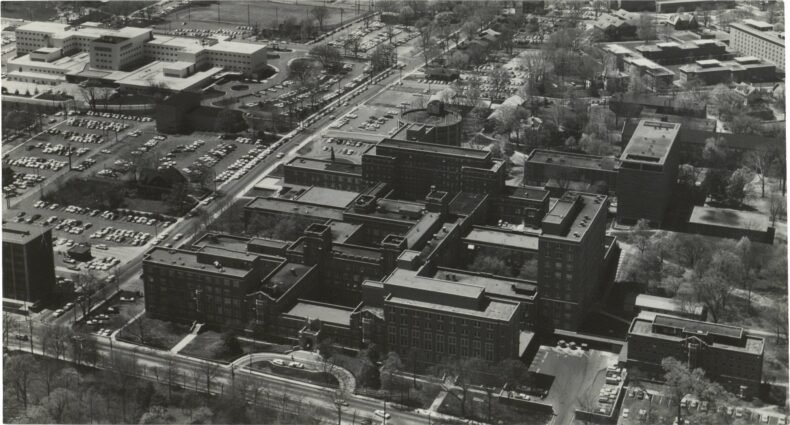

To gauge the remarkable expansion of VUMC in more recent decades, consider this: As late as 1977, VUMC — the hospital beds for adults and children, outpatient clinics, operating rooms, recovery rooms, labor and delivery, nursery, emergency department, pharmacy, research labs, library, cafeteria and more — was, with only a few exceptions, all inside the walls of MCN (We’re going to call it that here, for simplicity’s sake, even though it only acquired that name in 1980 when the new Vanderbilt University Hospital opened).

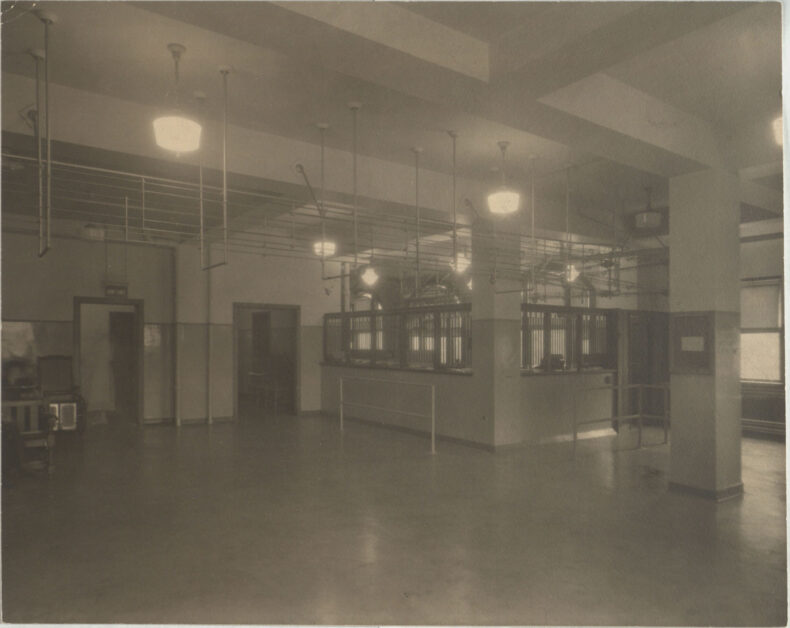

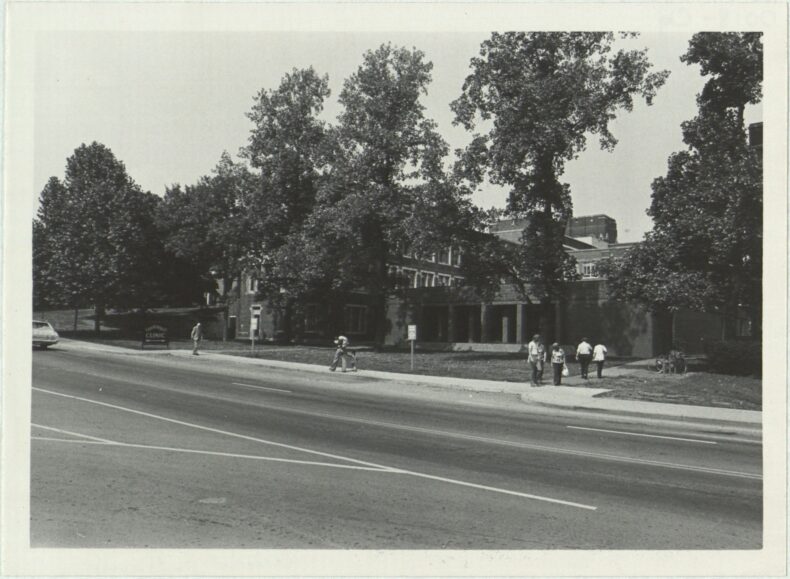

On the day MCN opened in 1925, it was as state-of-the-art as a medical facility could be.

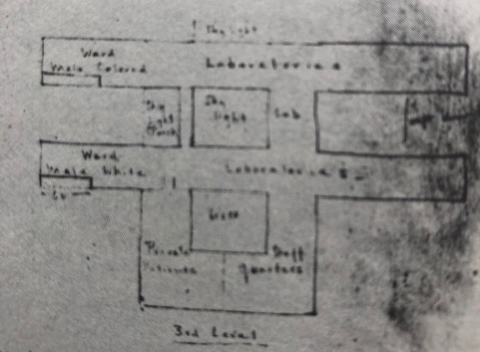

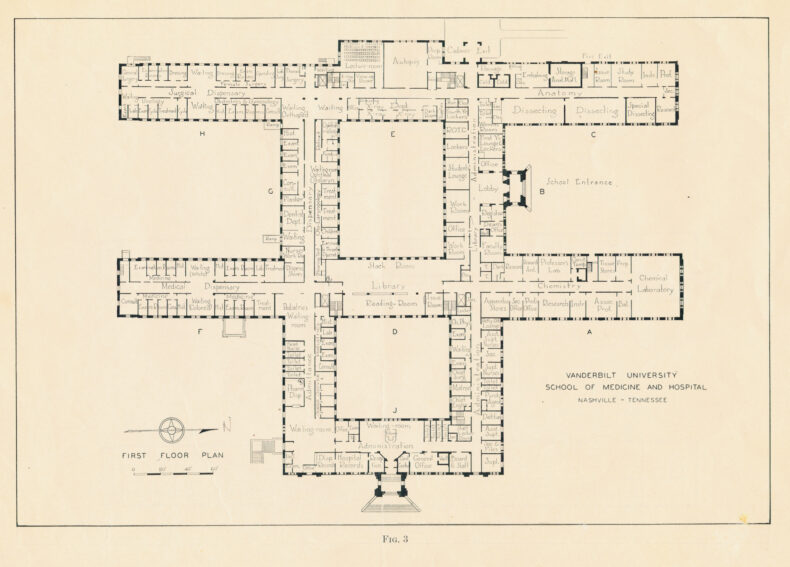

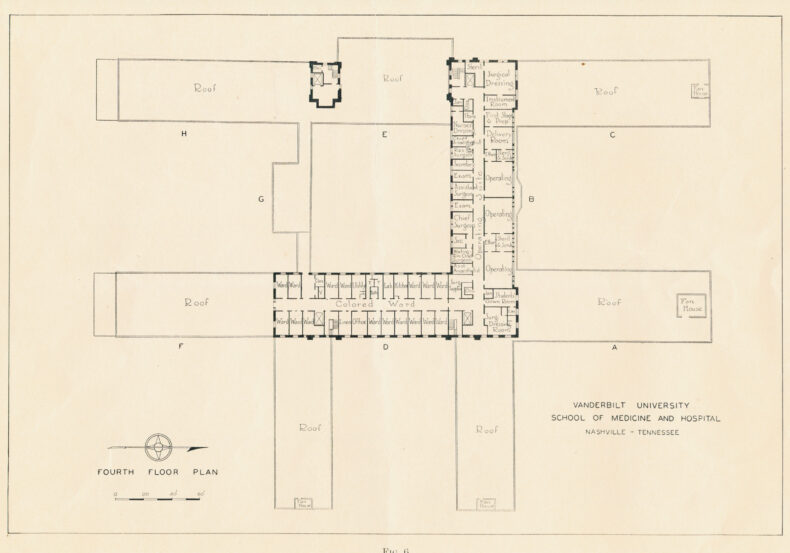

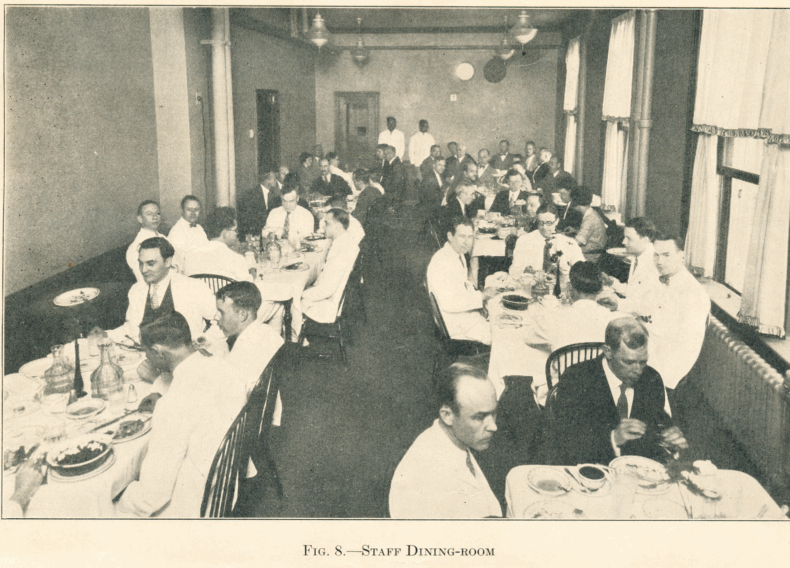

In its original footprint, it was a four-story structure with two east-west corridors, S and T (which stood for service and teaching), and intersecting north-south hallways, A, B and C. This tic-tac-toe board arrangement allowed almost all rooms to have a window — an important consideration that made daylight and fresh air available in days when electric lights were not especially powerful and air conditioning was still years in the future.

Rooms facing the interior of the building opened onto grassy courtyards, while the outside windows viewed the existing streets of Nashville. Garland Avenue was then a through street that ran just feet away from the hospital walls.

This innovative design was sketched by Canby Robinson, MD, who had come to Vanderbilt in 1920 as chair of the Department of Medicine and dean of the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine (VUSM). It was his vision to move VUMC from a small campus in downtown Nashville and to build a new, consolidated medical campus.

Robinson managed to persuade the chancellor and board of directors to provide $7 million, some of it from outside grants, to make his vision a reality. The architectural firm that brought his vision to life was Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch and Abbott (now Shepley Bulfinch) of Boston. Incidentally, $7 million is equivalent to about $128 million today.

Robinson wrote an article for the journal Methods and Problems of Medical Education in which he combined philosophy of how to educate physicians with practical considerations of the building itself.

“[The building plans] have been developed with the idea of stimulating a coordination of the various departments of the laboratories and hospital in such a way that an intellectual interrelation may be readily developed and cooperation of departments be effected,” he said. “The physical continuity of departments which has been established goes far to eliminate barriers between the preclinical and clinical studies, and allows all departments to exert a constant influence on the training of future physicians.”

He was also very descriptive of the appearance of the building.

“The total length of the building from north to south is 458 feet and from east to west 337 feet, its cubic content being 3,390,000 cubic feet,” he wrote. “The exterior of the building is treated in the collegiate Gothic style in red brick with limestone trim and detail.”

The expansion years

Within just a few years, VUMC had outgrown the new facility, and the first major expansion was completed in 1938. This was the addition of the D corridor to provide more space for patient rooms, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology.

Other major expansions to the original building continued through the decades. (This is not a complete list of every renovation or addition):

- 1954—The S.R. Light Laboratory for Surgical Research was added.

- 1961—A.B. Learned Laboratory opened, vastly increasing research space available to faculty and closing off a once open courtyard (now called the Chapman Quadrangle). The hallways were designated the U corridor (since it paralleled the S and T corridors), and it was later incorporated into Medical Research Building III.

- 1962—The Round Wing (Its original name, which didn’t stick, was the West Wing.) opened.

- 1964—The A corridor is extended to provide space for, among other things, the Medical Center Library.

- 1967—The Zerfoss Student Health Building was added to the rear of MCN.

- 1972—The Joe and Howard Werthan Building, which replaced the original facade of the 1925 building facing 21st Avenue South, was completed.

To the south of MCN was (and is) the Medical Arts Building, the first major part of VUMC not contained within MCN. It opened in 1955.

Next door to MCN to the north was (and is) another structure that opened in 1925, the building first housing the Vanderbilt School of Nursing. Now known as Mary Ragland Godchaux Hall, it included classrooms and offices (which it still has), and dormitory housing for more than 100 student nurses (which it does not).

Moving medicine forward in MCN

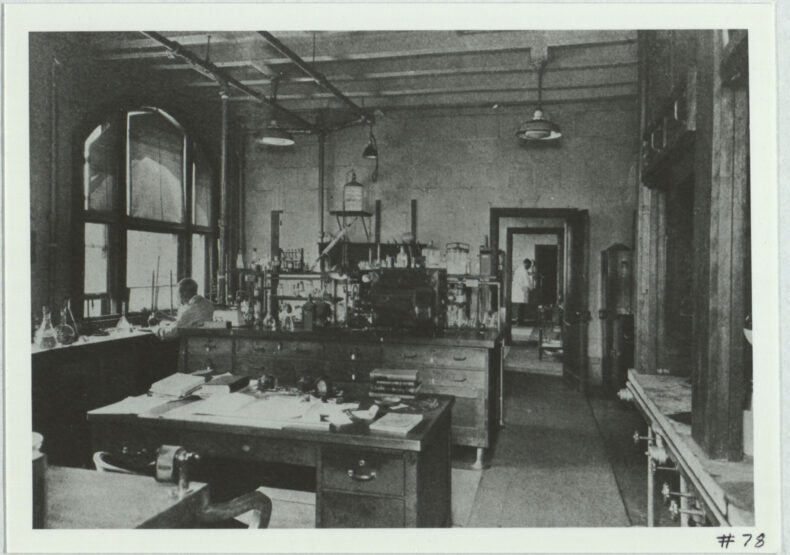

Some significant advances in American medicine occurred in this building. While this list is certainly not comprehensive, it shows that research, patient care and education have always existed alongside each other and pushed medical science forward.

- In 1933, Alfred Blalock, MD, and his research assistant Vivien Thomas conducted pioneering research leading to the first cardiothoracic surgery for infants born with “blue baby syndrome.” Their work was essential to the development of open-heart surgery.

- Beginning in the 1930s, Ernest Goodpasture, MD, who became dean in 1944, developed the method of culturing vaccines in chick embryos, which allowed the mass production of vaccines for smallpox, typhus and yellow fever.

- Care for infants was revolutionized nationally due to work by Mildred Stahlman, MD. Stahlman founded the Division of Neonatology and began the Vanderbilt Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in 1961, the first in the nation to make use of respiratory therapy for infants with damaged lungs.

- Elliot Newman, MD, used grants from the U.S. Public Health Service to do clinical research on several diseases. In 1960, this research led to the establishment of the federally funded Clinical Research Center which bears Newman’s name. It was the first such center in the country and continues to be housed in MCN.

The growing legacy

One way to better understand the legacy of MCN and underscore its importance to VUMC is to look at the buildings that now house the descendants of programs that originally existed in the 1925 structure.

The first of the series of buildings (except for the Medical Arts Building) was Rudolph A. Light Hall. The building, which opened in 1977, contained VUSM classrooms and laboratories. Langford Auditorium was soon added onto Light Hall.

This was followed by:

- Vanderbilt University Hospital (VUH) in 1980

- The Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Hospital (now Vanderbilt Psychiatric Hospital) in 1985

- The Vanderbilt Clinic in 1988

- Medical Research Building I (now the Ann and Roscoe R. Robinson Medical Research Building) in 1989

- The Kim Dayani Human Performance Center in 1989

- Stallworth Rehabilitation Hospital and the Medical Center East North Tower in 1992

- Medical Research Building II (now the Frances Williams Preston Building) in 1993

- The Annette and Irwin Eskind Biomedical Library (now the Annette and Irwin Eskind Family Biomedical Library and Learning Center) in 1994

- Medical Research Building III (now part of Vanderbilt University) in 2002

- Medical Center East’s South Tower, which houses, among other things, the Bill Wilkerson Center, in 2003

- Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in 2004

- Vanderbilt Eye Institute’s dedicated space in 2008

- Medical Research Building IV atop Langford Auditorium in 2008

- The Critical Care Tower addition to VUH in 2009

And then there are the many clinics and facilities that have grown beyond the Main Campus: Regional Hospitals, clinic locations including walk-in clinics, surgical centers, imaging centers and more.

Even MCN wasn’t finished growing when many of its original tenant programs relocated. The Institute of Imaging Science (built over what had once been the emergency department parking lot) opened in 2006, and a new vivarium was built on the seventh and eighth floors of the building’s A and AA corridors in 2008.

The newest addition in VUMC’s amazing story of growth, the Jim Ayers Tower, is scheduled to open for patients in October, only weeks after the 100th anniversary of MCN’s opening.

Through a century’s worth of growth and change, MCN remains a functioning, thriving building at the core of VUMC. It still contains key patient care facilities, a lecture hall, numerous research laboratories and administrative offices. The story of this amazing building is still being written.

(Thanks to James Thweatt and Chris Ryland of the History of Medicine Collections at Vanderbilt University for fact checking.)

Like any 100-year-old, Medical Center North has its stories, quirks and mysteries. Here are a few:

The TB Porch

In the original MCN, a porch for patients with tuberculosis ran between the B and C corridors on the second floor. Before the invention of antibiotics, there was no cure for tuberculosis, but fresh air was thought to be beneficial. Because of this, the original building had a porch adjacent to the TB ward. Above the porch, on the third floor, was a narrow walkway between the B corridor and C corridors. The second-floor porch and third-floor outdoor walkway were bricked-in during the 1950s, when antibiotics had TB on the wane, but are still visible above the awning of MCN that faces Medical Center Drive. The rows of windows that are the remnants of the old porch are on the second and third floors that cross between the corridors above the awning and back about 50 feet.

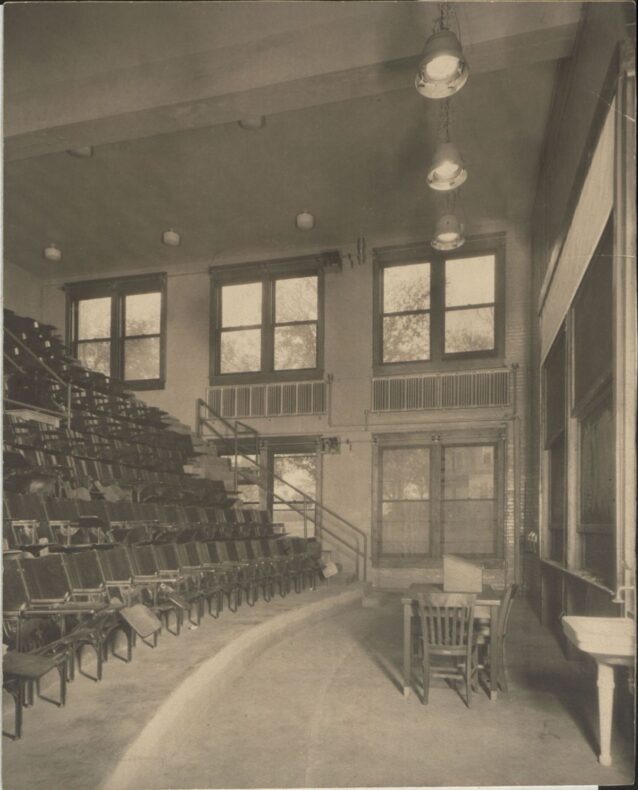

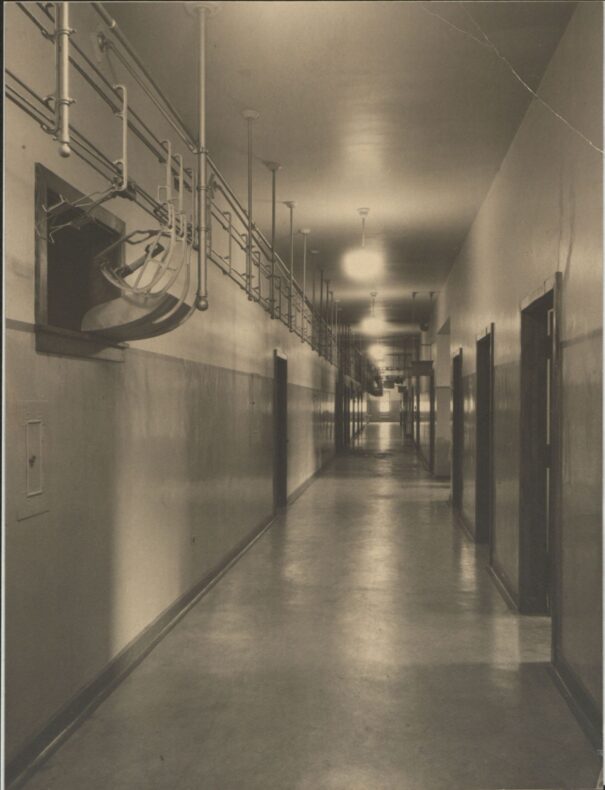

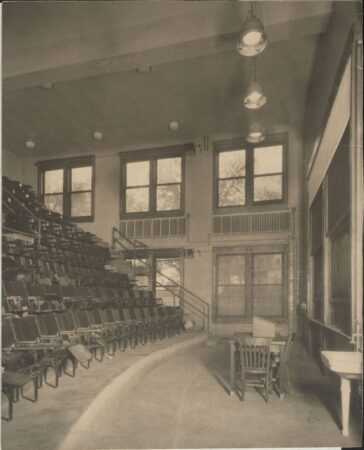

The Amphitheater at C-2209

This unusual two-story classroom with the porthole window in the door is the original big meeting hall for VUMC. The far wall was originally a two-story bank of windows looking out at the trees and grass behind the building, but those were bricked up when the D Corridor was added in a 1938 expansion. Until Rudolph A. Light Hall opened in 1977, the amphitheater was the largest meeting room at the Medical Center. The Nashville Board of Medical Examiners met here for years; part of the 1975 observance of Vanderbilt University’s centennial was held here; and this was the location of regular grand rounds for medicine and surgery. It has extra-wide doors so that patients’ gurneys could be rolled in while their cases were discussed. That also accounts for the alarming slope upward of the seating tiers; it was very important that everybody be able to see as well as hear.

Baa, Baa, Baby

The original design of MCN featured open, grassy courtyards framed by the wings of the building, which was built in a tic-tac-toe shape. When Mildred Stahlman, MD, was doing her groundbreaking research into the treatment of premature babies — work foundational for modern neonatal care — she needed a place to graze the sheep needed for the research. For several years in the 1950s and 1960s, patients and employees alike could glance out a window and see Stahlman’s flock.

Keeping the Flies Out of the Sterile Field

In the 1920s, electric lights were not as bright or efficient as today, and the operating rooms of the original MCN had large windows that let in daylight to help surgeons see. The building was not air conditioned in those days either, and on hot days the windows would be opened to provide ventilation. Someone in the OR would be given a flyswatter to keep insect intruders under control. The modern replacements of those extra-large windows can be seen from the Chapman Quadrangle by looking above the gothic doorway to the fourth floor.

The Chapman Quadrangle

The quadrangle was named in 2001 in honor of John E. Chapman, MD, who retired that year as dean of the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and his wife, Judy Jean, who taught for many years at both the Vanderbilt University School of Nursing and School of Medicine. This arched gothic doorway is the traditional entrance to the School of Medicine, and there are photographs of the faculty dating back to the 1920s snapped in front of this door. This quadrangle was also the site of many medical school commencement ceremonies.

This area was not always a closed courtyard. The wing of the building opposite the archway, the A.B. Learned Laboratory (now incorporated into Medical Research Building III), was built in 1960, closing off the courtyard. The street grid of Nashville once continued through this part of campus and just beyond the door on the far side of the quadrangle was a busy street. For many years this peaceful oasis was basically used as a parking lot.

Slippery Elms

The beautiful, stately trees in the Chapman Quadrangle are elms, which were once common all over the Eastern United States. Sadly, beginning in the early 1900s, a fungal disease known as Dutch elm disease began killing elms. Carried by beetles, the disease spread and by the 1970s had wiped out the majority of mature elms. These are among the few surviving elms of this age in the area, and the legend is that they survived because of the shelter provided by the buildings.

The Legend of Sugar Hill

There’s a concrete-floored, slanted basement hallway in MCN — D-0200 if you want to go find it for yourself. But here’s the thing — nobody has ever called this the D-0200 corridor. Once this hallway was known far and wide as Sugar Hill.

Here’s why: When MCN was both Vanderbilt University Hospital and the School of Medicine, there were a lot of young medical students, nurses and residents who spent many long nights in this building. This hallway was built on the slant, out of the way, dimly lit, and was used as a storage area for wheelchairs and gurneys.

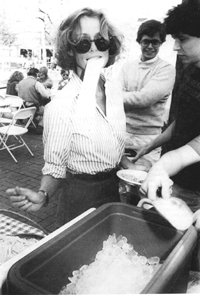

The Spooky Movie that Used MCN as a Set

In the winter of 1983, MCN was stalked by a killer. Luckily, this particular killer was fictitious, as the building was used as a shooting location for the TV movie “The Cradle Will Fall,” which starred Lauren Hutton, Ben Murphy, James Farentino and William H. Macy. The plot revolved around Hutton’s character, who is an assistant district attorney investigating the apparent suicide of a woman. It turns out that the death was not a suicide but…MUUUUUUURDER. And wouldn’t you know it? The chief suspect is the physician (Farentino) who is treating Hutton when she is hospitalized after a car accident.

MCN was under renovation, but parts of the building still pretty much looked like an old hospital, which is what it had been until three years before. That made it a perfect set for this spooky movie, based on the novel by Mary Higgins Clark.

The movie first aired on CBS the night of May 24, 1983, and can be found on some streaming services. Voters at the Internet Movie Database give “The Cradle Will Fall” 5.1 stars out of a possible 10.

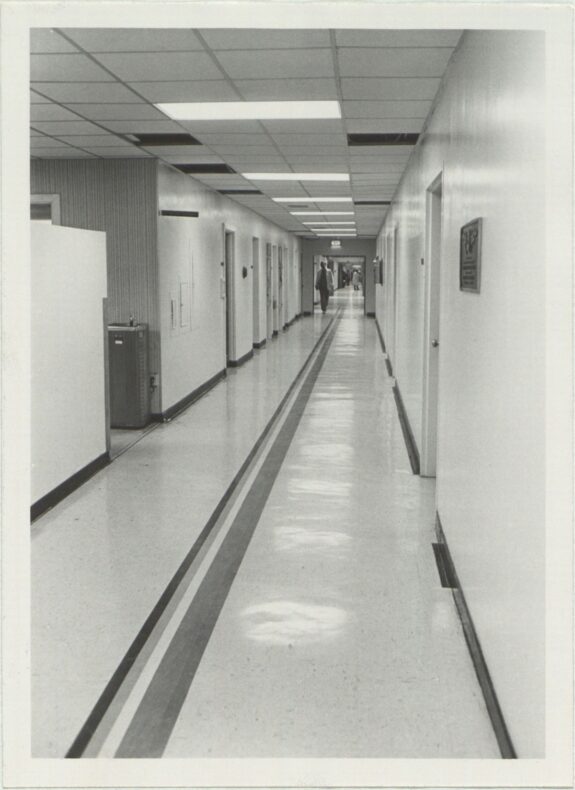

Step into the Twilight Zone

Near the B-4200 stairway is surely the most bizarre architectural feature in a building brimming with them. Step into the stairway, up the three steps to the left, and through the door. You will find yourself in a Twilight Zone corridor that takes you first down five metal warehouse-like steps, then around a corner to the right before passing through another door and resuming the T Corridor. It’s as though an addition was grafted onto the building and, after the fact, somebody realized things just didn’t quite match up, so this jury-rigged arrangement was put in place.

It gets weirder. Look to your left as you walk through the first part of that hallway. This brick wall used to be the exterior wall of the building. There is a door and several dark windows, complete with Venetian blinds. Look closer — the windows are dark because they were closed off from the other side by drywall, with the blinds left in place. Nobody has gazed out these windows, which once overlooked 21st Avenue South at the front of the building, since the addition called the Werthan Wing was added onto Medical Center North in 1972.

The Between-Floors Baby

The date was Sept. 17, 1971, and Barbara Viner and her husband, Vanderbilt medical graduate and resident Nick Viner, MD, had rushed to the hospital because Barbara was in labor. The young couple hurried into the ER and Barbara was immediately helped onto a gurney and wheeled to the elevator (its current designation is MCN-1) for the ride to the fourth-floor Labor and Delivery area.

Then things started happening fast. Too fast.

“All I remember is, they said, ‘He’s coming!’ and ‘There he is!’ — and I was still on the elevator,” Barbara remembered later. Their baby boy was born in the elevator. Barbara and Nick named their newborn son Daniel.

Twenty-three years later, in 1994, Daniel Viner followed in the footsteps of his father and came to medical school at Vanderbilt. Before he came for his interview, his mom had some advice for him: “When you get on the elevator, look up. You may recognize it.” Daniel Viner, MD, still practices otolaryngology in Nashville.

Who the Heck is Galloway?

If you look up at the outside wall of MCN that faces south, toward VUH, you’ll see a curious sight: the words, “Galloway Building” carved into the facade. That name is a goodwill gesture toward Nashville Methodists who had helped raise money for the construction of a downtown hospital that Vanderbilt was expected to occupy. Those plans changed; MCN was constructed instead; and some people were upset that the hard work and sacrifice that they had put into fundraising had been redirected. To help soothe the hurt feelings, the name of former Methodist bishop Charles Galloway was put on the building. There’s pretty much no evidence that anybody ever called MCN the Galloway Building.

Robert Vantrease’s Hippocratic Oath

Robert (Bobby) Vantrease was possibly the longest-serving employees in the history of VUMC. He began working part time in the Medical Illustration department as a Vanderbilt undergraduate in 1948, became full time in 1949, and retired in 2013 after 64 years of employment. He died just three years later in 2016. One of Mr. Vantrease’s early assignments is still on view in MCN. It is a hand-lettered rendering of the Oath of Hippocrates, a gift from the VUSM Class of 1951 to the school. That work, now yellowed around the edges with age, still hangs in a wood-and-glass case just inside the traditional entrance to Vanderbilt University School of Medicine in MCN. In the curlicue, decorative border, sharp-eyed observers can still pick out the inked signature of its then 24-year-old artist: “Robert M. Vantrease 1951.”

The “Guardian Spirit” of MCN

Trumpet player and bandleader Herb Alpert’s music has been part of the soundtrack of the past half century or so. He has had dozens of hit records, mostly with his band Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass, including five No. 1 albums and nine Grammy Awards.

Turns out, in addition to brass, he also worked in bronze.

Alpert is also a painter and sculptor, and one of his sculptures found just outside of MCN is titled “Guardian Spirit.” It was dedicated in 2001 and is one of four permanent installations of Alpert sculptures. The others are at American Jewish University in Los Angeles; the California Institute of Art in Valencia, California; and at the West Hills Community Center in West Hills, California.