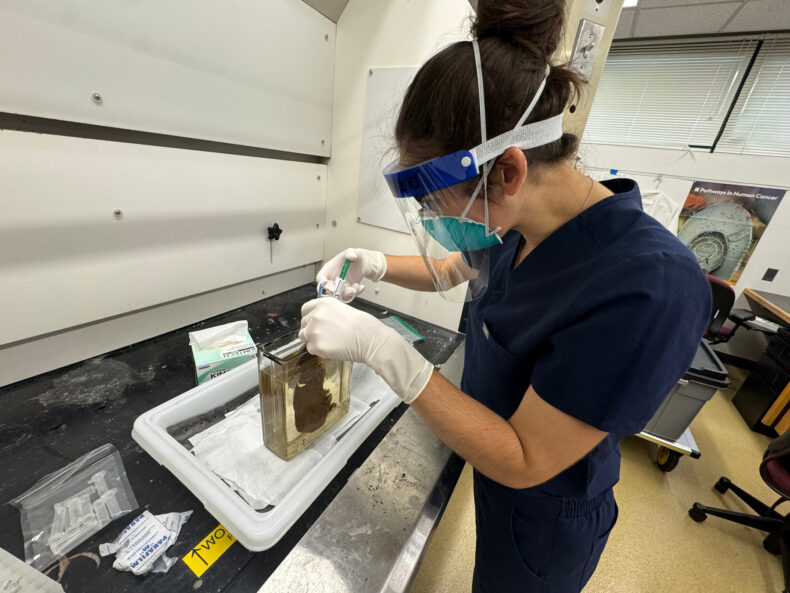

Katherine Van Schaik, MD, PhD, MA, positions skeletal remains in a CT scanner.

Katherine Van Schaik, MD, PhD, MA, positions skeletal remains in a CT scanner.

More than 60 million Americans are at risk of osteoporosis and other age-related conditions that weaken their bones and increase their risk of fractures, disability and death.

Yet the DXA scan, the current method for detecting low bone mineral density (BMD), is imprecise, and men do not routinely receive the low-dose X-ray technique.

Enter Katherine Van Schaik, MD, PhD, MA, a radiologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center who wants to change that picture.

Supported by a five-year, $749,000 grant from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health, Van Schaik and her colleagues are developing artificial intelligence/deep learning techniques which, when combined with epigenetic and molecular analyses, they hope will speed the diagnosis and improve the treatment of osteoporosis.

“Hip fracture mortality is very high, greater than most people recognize,” said Van Schaik, assistant professor of Radiology and Radiological Sciences. Approximately 24% of hip fracture patients die within a year of fracturing their hip. By five years after the fracture, that mortality rate doubles to 50%.

“That’s why improving our screening for bone mineral density, including identification of those most at risk of life-threatening hip fracture from low BMD, is especially important,” she said. “Vanderbilt is uniquely suited to pursue this kind of interdisciplinary work. All the pieces are here.”

Those pieces include the Vanderbilt University Institute of Imaging Science (VUIIS); ImageVU, a research archive of more than 1 billion radiology images; the Vanderbilt Lab for Immersive AI Translation (VALIANT); BioVU, one of the world’s largest repositories of genetic material; and the VANTAGE shared resource for advanced genomic technologies.

Van Schaik (pronounced “Shake”) arrived at VUMC in mid-2023 for a radiology fellowship after completing her residency training at Harvard and joined the faculty last year. Her clinical interest is inspired by an unusual endeavor — the study of old bones.

In 2016, while simultaneously pursuing her medical degree and a PhD in ancient history at Harvard, Van Schaik and a forensic radiology colleague used a portable X-ray machine to examine a collection of 18th- and 19th-century human skeletons interred in a London crypt.

Her inquiries eventually led her to the skeletons of 15 British sailors from the 19th century. CT scans revealed that these men, who lived into their 60s, experienced significant skeletal trauma, including multiple healed fractures. Yet compared to age-matched controls from the present day, their bones are stronger.

Despite nutritionally inadequate diets, exposure to disease and skeletal trauma, the sailors were, of course, physically active — as reflected in their strong bones. This suggests, said Van Schaik, that “load-bearing physical activity is really essential for managing bone health and for preventing bone loss, perhaps even more than we anticipated.”

During her residency, Van Schaik began to learn more about epigenetics, the study of modifications in gene expression not due to DNA mutations. Epigenetic changes are markers of physiologic stress.

Since the sailors had physiologically stressful lives but strong bones, Van Schaik wondered what their epigenetic profiles might look like. To complete the necessary molecular analyses, she obtained bone samples from the sailors.

Bones and teeth provide an excellent time capsule for preserving DNA, as well as the methylation patterns in the genetic code that reflect changes in gene expression.

With funding from the National Science Foundation, Van Schaik began to investigate — using computerized tomography (CT) scans and DNA analyses — the relationship between bone injury and epigenetic modifications associated with osteoporosis, in both historical and modern bone samples.

While the research may reveal more about the health of ancient mariners, epigenetic modifications can also be detected in DNA extracted from the blood of living people. Van Schaik is using ImageVU and BioVU to ask similar questions using CT scans and blood samples from modern patients.

“Wouldn’t it be great if we had a blood test to help assess hip fracture risk and to monitor treatment for low bone mineral density?” Van Schaik asked.

In conjunction with imaging, a blood test could identify patients who would benefit from therapy to prevent hip fractures and to determine whether they are responding to medications that can help rebuild bones.

Van Schaik has plenty of help. In addition to the NIH grant (K08AG088493), awarded in late August, and the resources and support that Vanderbilt University and VUMC provide to early-career researchers, including the Vanderbilt Faculty Research Scholars Program, several senior scientists have joined the effort.

They include VUIIS Director John Gore, PhD; VALIANT director and ImageVU principal investigator Bennett Landman, PhD; James Crowe Jr., MD, director of the Vanderbilt Center for Antibody Therapeutics; and Jeffry Nyman, PhD, director of the Vanderbilt Center for Bone Biology.

Van Schaik said Nyman, professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and Biomedical Engineering, and Gore, University Distinguished Professor and the Hertha Ramsey Cress Professor of Medicine, have been invaluable in image-based analyses, including assessing the sailors’ bone strength.

With Landman, University Distinguished Professor and the Stevenson Professor in the School of Engineering, Van Schaik is building an AI algorithm that can extract from a CT scan multiple metrics of bone health.

For the assessment of bone mineral density, CT is a superior technique compared to DXA, but its high radiation dose makes it prohibitive for routine screening. A machine-learning method, however, could pull information about a patient’s bone health from CTs ordered for other reasons. This is called “opportunistic” imaging.

Van Schaik and Landman have also been collaborating on efforts to evaluate the bone health of Egyptian mummies through analysis of CT scans.

On the molecular analysis front, Crowe, University Distinguished Professor of Pediatrics and the Ann Scott Carell Professor, is guiding the development of methods for the epigenetic analysis of DNA samples from living individuals, as well as the 19th-century sailors.

An expert on how the body responds to infection, he also will help Van Schaik develop methods to assess — in historical remains — inflammation and response to infection, which can accelerate aging and age-related diseases, including osteoporosis.

Other contributors to the research include Kris Burkewitz, PhD (Cell and Developmental Biology), Nancy Cox, PhD (Genetic Medicine and Clinical Pharmacology), Emily Hodges, PhD (Biochemistry), Seth Smith, PhD (associate director, VUIIS), Jesse Spencer-Smith, PhD (Data Science Institute), and Rick Wright, MD, (chair, Orthopaedic Surgery).

“The collaborative ecosystem here is really extraordinary, unlike anything I’ve encountered anywhere else,” Van Schaik said. “The enthusiasm, the expertise, the work ethic and, also, the genuine warmth make completing these types of projects not only possible but deeply enjoyable.

“We’re all learning together,” she said, “contributing the skills and knowledge we have to getting answers to questions that are not only interesting because they have to do with people who lived a long time ago, but also very relevant because they directly impact the patients we’re seeing on a daily basis.”