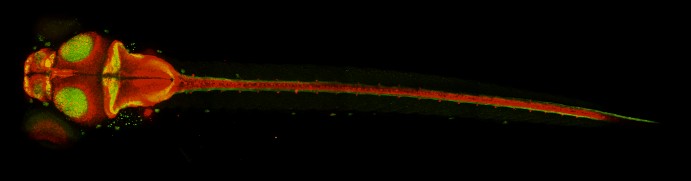

The cranial muscles of a zebrafish glow in this image from the Knapik Laboratory.

The cranial muscles of a zebrafish glow in this image from the Knapik Laboratory.

While still in medical school, Ela Knapik, MD, decided to devote her career to collaborating with others to solve the “jigsaw puzzles” of disease.

As she puts it, “I can’t help everybody, because it’s just me with two little hands. But if you provide knowledge to as many people as you can … they will be your hands.”

Today, Knapik is a professor of Medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Her lab is known internationally for its use of modern genome-editing techniques in a powerful animal model — zebrafish — to unravel the often-convoluted genetic roots of rare, and not so rare, diseases.

Complex diseases, in Knapik’s view, are like multidimensional jigsaw puzzles. Researchers try to put “a truckload of pieces (together) without knowing how many pieces are needed and what the final image looks like,” she said. To complete the puzzle correctly, they first must know what each piece does.

This approach — deciphering the function of individual genes — has helped Knapik’s team determine what drives rare developmental disorders such as Anderson disease, a lipid malabsorption syndrome. It also has advanced understanding of more common diseases, including atrial fibrillation.

“This is my calling, my excitement, my joy,” Knapik said. “Providing information on basic gene function can better patients’ lives.”

From medical school, Knapik’s postdoctoral path to discovery led to the lab of famed developmental biologist Peter Gruss, PhD, at the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, Germany.

Encouraged by her mentors to move to the United States where she would have “many opportunities to do science the way you want to,” she secured a position at Massachusetts General Hospital with Harvard cardiologist Mark Fishman, MD, whose notable zebrafish studies have advanced understanding of circulatory system development and disease.

Essential cargo

In 2004, Knapik was recruited to Vanderbilt. Here she continued her work in a lab on the campus of Vanderbilt University Medical Center lined with zebrafish tanks.

Zebrafish are only about an inch long. But because their eggs are fertilized outside of the female’s body, their transparent, rapidly developing embryos have become an efficient and inexpensive model for studying genetic and environmental factors that influence early development of vertebrates.

Added to that is a revolutionary genome-editing technique, called CRISPR-Cas9, which has made it easier for researchers to introduce genetic mutations in model organisms such as zebrafish and study what happens.

Knapik and her colleagues use genetically modified zebrafish to study intracellular, gene-driven transport systems that recognize, package and transport essential “cargo” proteins during development and throughout life. They have shown how genetic mutations can disrupt critical protein transport pathways and cause severe musculoskeletal deformities.

In 2010, they reported that a mutation in the sec24D gene produced zebrafish with shortened bodies, deformed heads and kinked pectoral fins. An international research team subsequently linked variants of the corresponding human gene to osteogenesis imperfecta, a syndrome of skeletal malformations in children commonly known as “brittle bone disease.”

Fast-forward a decade: Knapik’s team was investigating ric1, another gene that, when mutated, causes skeletal defects in zebrafish, when they read about several children in Saudi Arabia who had pediatric cataracts. Their unusual condition was associated with a mutation in RIC1, the human version of the zebrafish gene.

Intrigued, Knapik went to VUMC’s biobank, BioVU, to learn more about the human gene. BioVU houses about 350,000 DNA samples linked to donors’ de-identified electronic health records. It is the world’s largest such collection based at a single academic center.

Using a computational method developed by Nancy Cox, PhD, founding director of the Vanderbilt Genetics Institute, and her colleagues, Knapik generated a list of clinical characteristics associated with reduced expression of the human RIC1 gene.

When the Saudi clinicians reevaluated patients with RIC1 mutations, they discovered that eight children from two related families shared other characteristics that mirrored what Knapik’s group had observed in the ric1-altered zebrafish.

The new disease was named CATIFA, an acronym of its core characteristics: cleft palate as well as cataracts, tooth abnormality, intellectual disability, facial deformity and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Connecting the pieces

In 2019, Knapik and her colleagues were invited to join an investigation of four children from two related families in Turkey who had smaller-than-normal head size, cataracts, severe developmental delay, intellectual disability and epilepsy.

Three children in one family died in infancy. The fourth child, a cousin, had other problems, including hearing loss, liver dysfunction and difficulty moving due to a severe loss of muscle tone. He was hospitalized numerous times, received tube feeding, and while the study was still underway, he died before his 5th birthday.

Suspecting a genetic abnormality, the Turkish physicians, working with colleagues in Germany, collected and sequenced DNA samples from the two families — and got a hit. Both sets of parents carried a variation in SEC24C, a member of the SEC24 gene family.

At that point, the Germans advised their Turkish colleagues to contact Knapik: “You have to go to Ela. She is the world expert.”

Knapik had long suspected that SEC24C mutations would cause disease in humans. Now, finally, she had a chance to find out. Her colleagues, led by senior research scientist Dharmendra Choudhary, PhD, research assistant Cory Guthrie, and graduate student Taylor Nagai, used genome editing to functionally inactivate the corresponding gene in zebrafish embryos.

Zebrafish lacking the gene had smaller brains, cataracts, and could not swim normally. These characteristics mirrored the human condition.

The VUMC researchers passed their findings back to the Germans, who, with colleagues in Canada, validated the zebrafish findings in human tissue studies. They showed that a loss of function of the human SEC24C gene disrupted the trafficking and modification of proteins that are transported along vital intracellular pathways.

It had taken four teams of physicians and scientists on three continents, but the puzzle was now complete. It was a new human disease. And zebrafish had provided a key part of the solution.

These findings, reported in March 2025, have implications far beyond solving the mystery of a rare disease, Knapik said. This approach — engaging a multidisciplinary, global cross talk to interpret a clinical report with the help of animal models and human tissue studies — may help advance the treatment of more common and complex conditions such as movement disorders and epilepsy.

Knapik attributed her lab’s success to VUMC’s highly collaborative and resource-rich research environment, and to the steady financial support she received over the years from the Zebrafish Initiative of the Vanderbilt University Venture Capital Fund and from the National Institutes of Health.

The latest discovery illustrates the importance of two other essential elements of fundamental research — sharing knowledge and collaboration.

“We need more of that,” Knapik said. “We need teams from different backgrounds coming together to solve the puzzles of rare and common diseases.”