When Gerald Hickson, MD, and James Pichert, PhD, knocked on their first professional’s door in the 1990s, they were venturing into uncharted territory. There was no playbook for addressing unprofessional behavior in health care — only a malpractice insurance crisis threatening the field, skyrocketing claims costs, and leadership at Vanderbilt who recognized that disrespect modeled by a small number of faculty threatened the quality of care delivered and were willing to address the challenge.

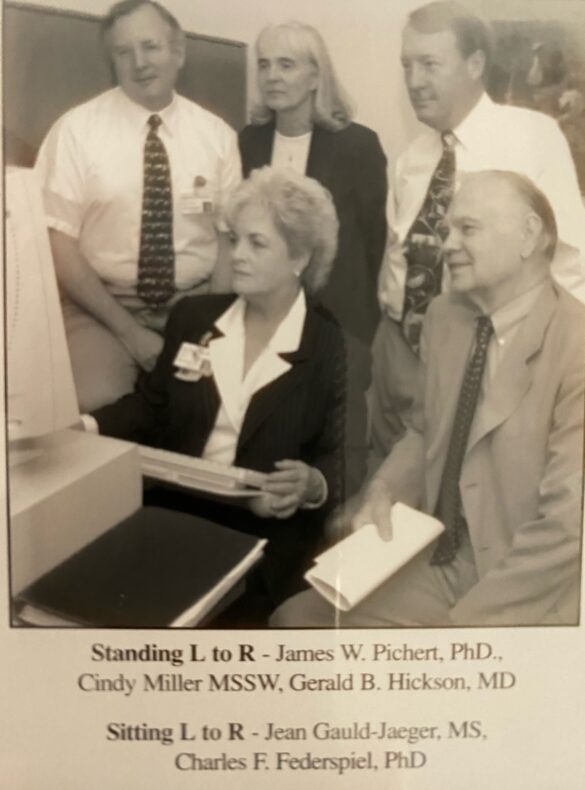

Hickson, Joseph C. Ross Professor of Medical Education and Administration, professor of Pediatrics, and founding director of the Vanderbilt Health Center for Patient and Professional Advocacy (CPPA), and Pichert, co-founder of CPPA and professor emeritus of Medical Education and Administration, teamed up with biostatistics pioneer Charles Federspiel, PhD, and Cynthia Miller, MSSW, to build an integrated assessment, training and follow-up workflow that would change the course of what it means to be a professional in health care.

Three decades later, CPPA has become a cornerstone of health care culture transformation, serving more than 300 sites in 29 states, Australia, and other countries encompassing more than 225,000 clinicians.

“These 30 years have been made possible, in large measure, because of the support of our vice chancellors and senior leaders who were willing for us to address what had been identified as a problem, but for which there was not a standard approach,” Hickson reflected.

From Crisis to Innovation

In the early 1990s, health care faced a malpractice crisis. Lawsuits were rampant; insurance costs were skyrocketing; and some insurers were quitting the business altogether. Hickson’s pioneering research between 1980 and 1994 revealed an uncomfortable reality: Studies at Vanderbilt and in Florida showed that a small subset — 2% to 8% by specialty — accounted for 50% to 70% of medical malpractice claims and dollars.

“Thirty years ago, the medical field was very concerned with a crisis of insurability,” Pichert explained. “It wasn’t just the outcomes. It was the way patients felt they were treated — they felt a relative lack of respectfulness, listening, care and concern.”

Pichert, an educational psychologist specializing in teaching and learning, brought crucial expertise. His research methodology could parse patient complaint narratives and reliably identify specific issues that mattered most. “We could turn anecdotes into data,” he said — a phrase that became central to CPPA’s approach.

Federspiel, the late founder of Vanderbilt’s biostatistics department, provided essential analytical rigor.

“Chuck was always concerned that we help individuals who were off track to get back on course as professionals,” Hickson said. “Chuck always listened, waited for the right moment, and then offered that thoughtful comment, that piece of insight that we all needed to hear.”

Beginning in 1995, the team received funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to develop and pilot test an “Early identification and response model for doctors at high risk of risk management activity” at Vanderbilt and four community medical centers. The Patient Advocacy Reporting System® (PARS) evolved from this work, and in 2002, the group published “Patient Complaints and Malpractice Risk” in JAMA, demonstrating the relationship between patients’ perceptions of disrespectful care as shared with a health system’s Office of Patient Relations and decisions to contact a lawyer and file suit.

The model was simple — or based on common sense — but has had a profound impact on so many clinical team members: Use data to identify patterns, then have trained peer messengers deliver awareness interventions with empathy. Hickson recalled an early intervention where a department chair who was on the receiving side of an awareness intervention conversation threw the documentation folder across his office.

Two weeks later, that same chair called his peer messenger, also a chair, now ready to engage — an early situation that informs how peer messengers are trained to deliver feedback today.

“The majority of individuals on the receiving side of the intervention will respond professionally — they may remain silent or may be embarrassed, and on a very rare occasion toss a folder,” Hickson said. “The key is to give your colleague some information so they can review, just pause, perhaps gain insight, reflect and as most do, self-regulate.”

Building the Training Model

When asked about training for peer messengers, Pichert recalled that “Dr. Hickson and I looked at each other and said, ‘Oh, well, we’ll get together and we’ll do that training,’ but we really hadn’t come up with it at the time.”

The training evolved from role-plays between the founders to comprehensive scenarios where proposed messengers practiced responses. “I can cry on command. I can scream on command,” Pichert would tell trainees, preparing them for every possible reaction.

The training manual grew to include dozens of pages covering common pushbacks and responses. Messengers could withdraw at any point with no penalties, and they always had direct phone access to the founders. Many became institutional leaders — C. Wright Pinson, MBA, MD, who would become Vanderbilt Health’s Deputy CEO and Chief Health System Officer, was one of the first messengers.

The Center Takes Shape

CPPA was formally created in 2003 as the home of PARS and the later Coworker Observation Reporting System℠ (CORS). Under these programs, CPPA has now analyzed more than 4 million patient stories and 425,000 co-worker observations or concerns of disrespectful or unsafe care, with the systems associated with 82% and 89% reductions in complaints, respectively.

Proven Impact

Evidence has mounted over the decades. A study in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery examined a multisite orthopaedics practice that implemented PARS in 2009. Over 12 years, malpractice claims costs for 42 high-risk clinicians identified (of 260 total) fell by 83%, while overall per-professional claims costs dropped by 87%. Thomas Doub, PhD, assistant professor of Pediatrics and CPPA faculty member, noted at the time that while the observational study couldn’t prove cause and effect, the organization-wide commitment to professional accountability appeared to have clear impact.

Additional research demonstrates that patients of surgeons with higher numbers of co-worker reports about unprofessional behavior are more likely to experience complications, and trauma patients who received care from services with high proportions of unprofessional physicians faced a 24% increased risk of death or complications.

Structured Response to Serious Concerns

CPPA has also pioneered the “huddle” approach to effectively and efficiently address reports of behaviors that require additional fact-finding and, if warranted, investigation.

A study published in BMJ Leader examined five health care systems conducting 219 huddles for the most serious concerns like hostile work environment, physical violence, and potential sexual boundary violations. Cynthia Baldwin, MS, RN, CPHRM, senior associate in Pediatrics and CPPA faculty member who led that research, explained that without structured huddles, “siloed information and processes can occur,” leading to confusion or delays in addressing serious matters.

Expansion and Impact

William Cooper, MD, MPH, who succeeded Hickson as CPPA’s director and in the fall of 2025 became Vanderbilt Health’s first Senior Vice President for Professionalism and Clinical Excellence, has led the center’s growth while bringing increased research rigor.

In 2024, Vanderbilt Health extended PARS and CORS to its three Regional Hospitals. Adam Huggins, MD, MMHC, chief of staff for Vanderbilt Regional Hospital Division, said at the time that the programs had been “transformational,” bringing “an objective and data-driven process to improving professionalism and overall culture.”

Organizations nationwide have achieved remarkable results, including Mount Sinai Health System’s 95% response rate to professionalism concerns — among the highest of any CPPA partner site.

Looking Ahead

As CPPA enters its fourth decade, Hickson sees new challenges ahead. Rising distrust in medical professionals means health care teams will face increasingly difficult interactions.

“As we look to the future, I’m struck by the continued relevance of Drs. Hickson, Pichert and Federspiel’s work,” said Cooper, the Cornelius Vanderbilt Professor of Pediatrics and Health Policy. “With the increasing complexity of health care, it’s essential that health care organizations ensure that all team members can be the best version of themselves. Organizations that survive and thrive in this environment will get that right, and we’ve got the tools and processes to help them along their journey.”