Julia Sheffield, PhD (photo by Susan Urmy)

Julia Sheffield, PhD (photo by Susan Urmy)

Julia Sheffield, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, has dedicated her career to solving the mysteries of psychosis.

As a clinician, Sheffield, the Jack Martin, MD Research Professor in Psychopharmacology and assistant professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, wants to help individuals with schizophrenia overcome the delusions, paranoia and voices that torment them.

As a scientist, she is fascinated by delusions — how beliefs are formed, how they become entrenched, and why, after seeing two red cars, for example, a person becomes convinced that he or she is being followed.

Everyone has some degree of paranoia. But only 1 in 100 will develop full-blown psychosis. Most patients respond to treatment, primarily antipsychotic medication and cognitive behavioral therapy, but access to CBT is limited and the relapse rate is high.

Lately Sheffield has been investigating “prior expectations of volatility,” the belief that your environment is frequently changing — more volatile than it really is — and how this thinking fuels “persecutory delusions” that the world is out to get you.

Persecutory delusions occur in more than 70% of individuals with psychosis. They are among the most difficult delusions to treat. Sheffield believes that outcomes may improve by focusing on prior expectations of volatility — also called volatility priors.

A key piece of evidence linking volatility priors to the development of persecutory delusions and psychosis can be found in studies of individuals who were maltreated as children — physically or emotionally abused or neglected or sexually abused.

Childhood maltreatment is a well-documented risk factor for psychosis and schizophrenia. Research suggests that prior experiences shape how new information is interpreted and integrated into one’s view of the world. “You can imagine,” said Sheffield, “that your expectations of how unpredictable your world is are shaped by your childhood experience.”

In a paper published last year, Ali Sloan, MEd, a doctoral student in clinical psychology at Vanderbilt, Sheffield and colleagues reported that individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders exposed to harm during childhood expected their environments to be more volatile, potentially facilitating the development of persecutory beliefs.

“Volatility priors may serve as a potential treatment target for individuals exposed to childhood maltreatment to prevent the onset or attenuate the severity of psychotic symptoms, including paranoid thinking,” the researchers concluded.

Learning to feel safe

With support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health, Sheffield is testing whether cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis can help clients readjust their volatility priors.

Research has shown that directly challenging delusional beliefs will only make them stronger and more elaborate. Instead, CBT for psychosis is a nonconfrontational approach that, by emphasizing, helps clients update their beliefs about the world.

The VUMC approach, based on the “Feeling Safe Program” developed by British psychologist Daniel Freeman, targets specific factors that contribute to persecutory delusions, including worry, safety behaviors, avoidance and hallucinations (such as hearing voices).

Clients are encouraged to examine beliefs and behaviors that they agree are bothersome. “Do things that make you feel better,” Sheffield suggests. “Change things that make you feel worse.”

Carefully guided excursions help clients test whether their environment is more stable than they thought. The goal is to help clients shift and shape prior expectations, so that updated beliefs about safety eventually outcompete the persecutory ones.

The effectiveness of CBT for psychosis can be understood through “predictive coding,” a theory that the brain constantly makes predictions based on prior beliefs that are tuned by past experiences.

Prediction errors are encoded in dopamine signals in the striatum, a center of coordinating movement, motivation and learning, and in the midbrain. These signals, in turn, are supported by a broad network of brain regions including the insula, which is involved in cognition, self-awareness and emotion.

In a randomized clinical trial of 62 individuals with schizophrenia, Sheffield and her colleagues compared two psychotherapeutic modalities — CBT for psychosis and “befriending” therapy — for their ability to reduce the level of volatility priors and persecutory delusions.

Schizophrenia is profoundly isolating. “That’s why (befriending) works so well,” Sheffield said. In a once-a-week session with a therapist, “you hang out with another human for an hour … a nice person who doesn’t talk to you about your symptoms … It can help (you) reconnect.”

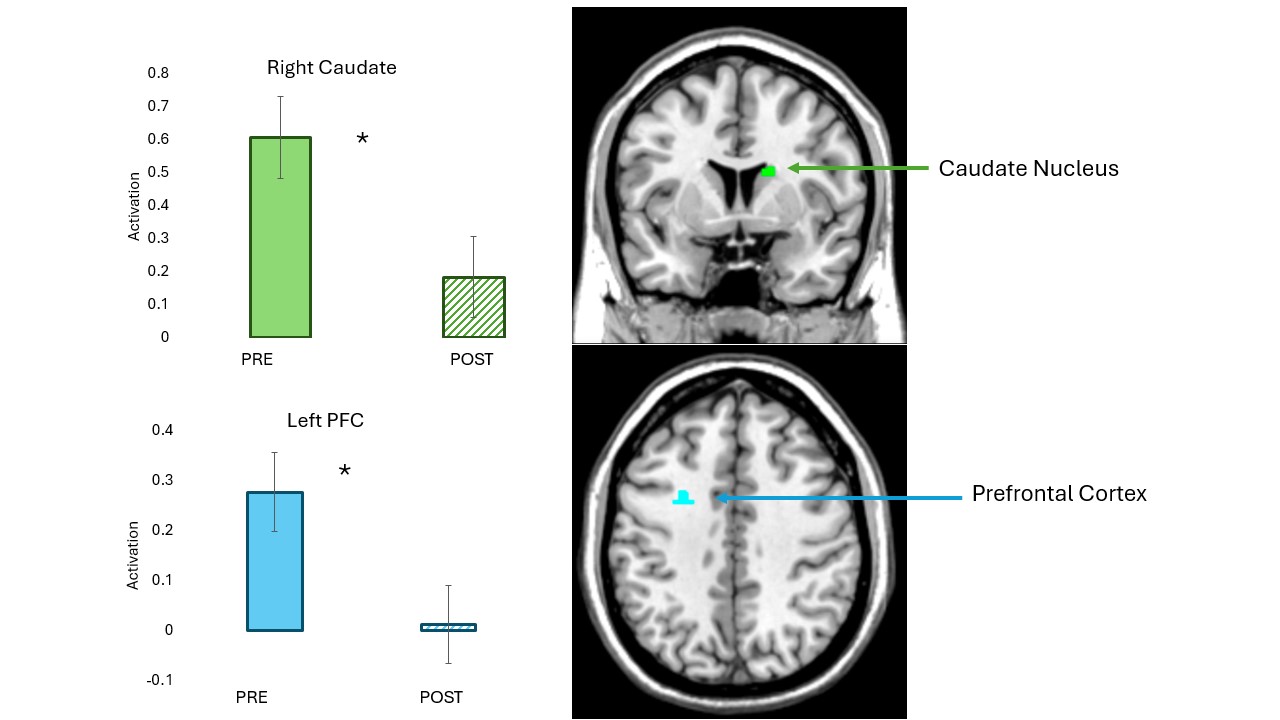

To estimate the level of volatility priors, 35 participants in the clinical trial were asked to perform a cognitive task while their brains were scanned by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) before and after eight weeks of therapy.

“It’s very unusual for people in clinical trials to have neuroimaging pre- (and) post,” Sheffield said. “This was another opportunity for us to ask, is psychotherapy doing anything in the brains of people with schizophrenia?”

A game of cards

During fMRI, participants were asked to choose from among three decks of cards presented on a computer screen which deck had the most winning cards. Because the winning deck changed during the task, the “players” had to change decks to keep winning.

People with schizophrenia do more “win-switching.” Because their volatility priors are elevated, they are more likely than a person without psychosis to swap decks even though they just won with one. This can make it more difficult for them to track where they are in the game.

“If you expect more volatility in your environment, you behave in a way that’s less predictable, and that makes the environment seem more volatile than it actually is,” Sheffield said. “I suspect there’s some sort of feedback loop that’s happening.”

Over the course of the study, the researchers found that both therapies — CBT for psychosis and befriending therapy — reduced volatility priors and improved persecutory delusions, as measured by clinical observation, cognitive testing and brain activity.

“In schizophrenia, it’s been shown there’s too much activation in the striatum, particularly in the caudate, which is a dopamine-rich region,” Sheffield said. “It’s hyperactive. What we wanted to see was (that activity) go down, which is what we saw.”

Their findings, published in June in the journal JAMA Network Open, showed that activation in the brain changed with therapy, and in relation to volatility and psychosis.

The study, which used computational modeling to estimate volatility priors, is unique, Sheffield said, because it measured three levels of response: neurobiological (brain), cognitive (testing), and psychological (clinical outcomes). The findings also challenge the perception that therapy for schizophrenia doesn’t really work.

“We did eight weeks of therapy, which is not very much, with some people who have gotten almost no therapy their whole life despite having schizophrenia for 30 years, and they got better clinically. There was a change in their brain activation and in their behavior,” Sheffield said.

“That to me is very exciting,” she said, “that therapy for schizophrenia, and for delusions specifically, can help people change their behavior, change their brain.”

A ray of hope

Last summer Sheffield received a five-year, $3.8 million grant from NIMH to extend and validate her group’s findings. A study of 120 individuals with schizophrenia who will receive 16 weeks of CBT for psychosis is underway.

If confirmed, this would lead the way for the first treatment for volatility priors. And it would offer a ray of hope for many families.

Schizophrenia is still highly stigmatized. Despite common misconceptions, “it’s extremely uncommon for people with schizophrenia to be violent,” Sheffield said. “People with serious mental illness are more likely to be the victim of a crime than a perpetrator.”

Increasingly, schizophrenia is seen as a developmental disorder that often arises during the late teens and early 20s, predominantly in men.

A recent high school graduate may be preparing to go to college, for example, when he starts feeling odd or hears things that others cannot hear. He can’t hold a job. He lives with his parents. Or ends up on the street.

In an interview published in the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center Notables newsletter last year, Sheffield said she hoped improved treatment will help individuals with schizophrenia reconnect with others, “view themselves as important members of their communities … and (build) a happier and more fulfilling life.”

Sheffield, who earned a PhD in clinical psychology from Washington University in St. Louis in 2018, came to Vanderbilt for postdoctoral training before joining the faculty in 2020.

Her study is part of the Vanderbilt Psychotic Disorders program, known for the excellence of its research and coordinated specialty care. “Vanderbilt is one of the only places in the country that offers empirically supported treatment specifically designed for persecutory delusions,” she said.

Sheffield and Sloan are co-authors of the paper on volatility priors with Baxter Rogers, PhD, Simon Vandekar, PhD, Jinyuan Liu, PhD, Margaret Achee, PhD, Kristan Armstrong, PhD, Neil Woodward, PhD, Aaron Brinen, PsyD, and Stephan Heckers, MD.

The study was supported by NIH grants K23MH126313 and R01MH127018.